Forefoot: Leveraging Ground Interaction for Efficient Movement

- Updated - June 16, 2025

Every step we take is a finely tuned interaction with the ground, and the forefoot plays a defining role in how efficiently that exchange unfolds. Far from being a passive structure, the forefoot is a dynamic lever. It helps us transition weight, maintain momentum, and support whole-body coordination.

This region is more than just the ball of the foot and toes. It is a critical interface between the body and the ground during movement, adapting to load, stabilizing posture, and guiding efficient motion. Forefoot pain can significantly impact this efficiency, affecting conditions such as metatarsalgia (pain in the ball of the foot), sesamoiditis, and Morton’s neuroma.

Whether you’re a movement professional or seeking better alignment and ease in motion, understanding how the forefoot functions can reshape your walk, run, and even stand.

Anatomy and Function: Understanding the Forefoot

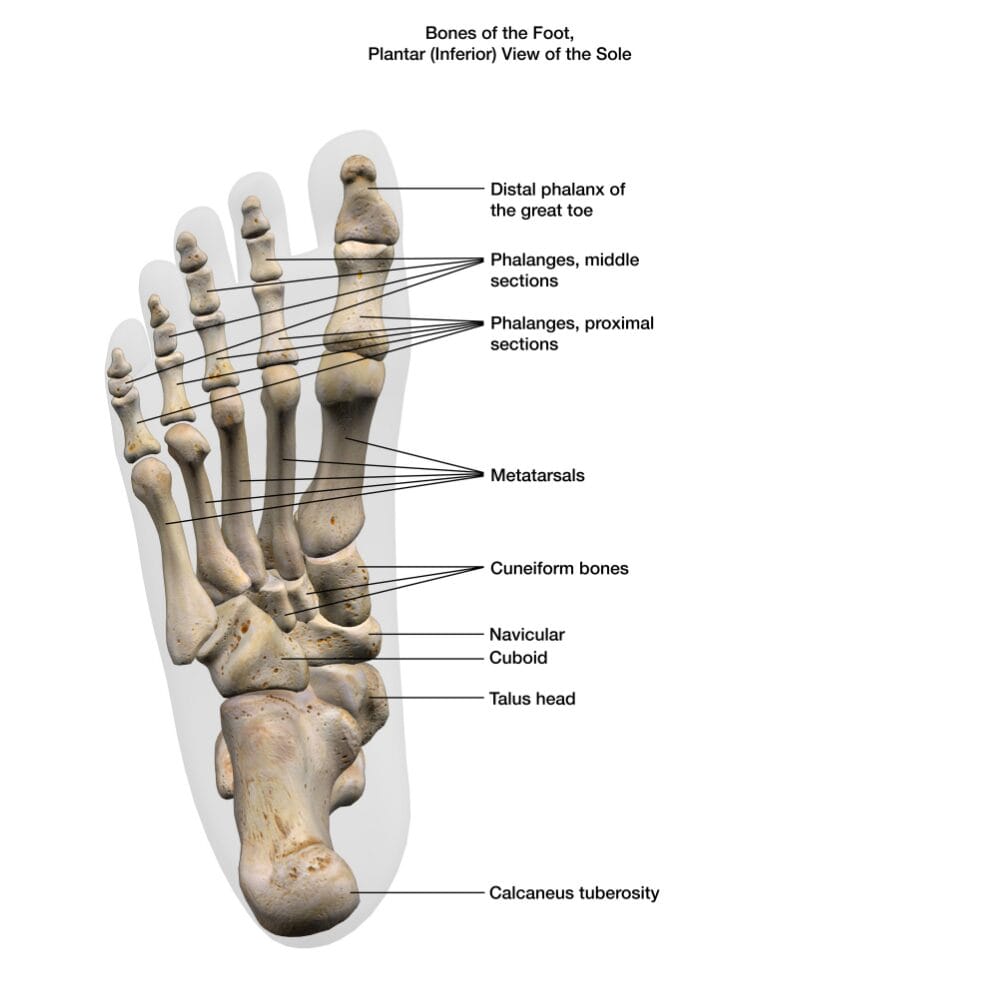

The forefoot is the front third of the foot. It includes the five metatarsal bones, the phalanges (toes), and the surrounding muscles, ligaments, blood vessels, and connective tissues that support movement and load transfer. The soft tissue structures in this area are crucial for supporting various joints and maintaining overall stability during movement.

This region is essential for walking, running, standing, and balancing. As the final segment of the foot to interact with the ground, the forefoot plays a pivotal role in translating body weight into forward motion, absorbing shock, and adjusting to uneven surfaces.

What's in the Forefoot? Understanding the Metatarsal Bones

- Metatarsal heads (the ball of the foot): These form the base of the forefoot and provide a platform for weight-bearing during the late stance phase of gait.

- Phalanges (toes): These small but important bones help distribute pressure and guide motion. The big toe (hallux) consists of a distal phalanx and a proximal phalanx, which are crucial for propulsion and alignment. The other toes include a distal phalanx along with additional phalanges, contributing to the overall structure and function of the foot.

- Plantar fascia and intrinsic foot muscles: These tissues support the medial longitudinal arch, regulate stiffness and adaptability, and help the foot respond dynamically to load.

Discover a practitioner near you.

Looking for a practitioner near you? Our extensive network of qualified professionals is here to help you.

Metatarsal Bones and Phalanges

The metatarsal bones and phalanges are crucial components of the forefoot, playing a vital role in weight-bearing and movement. The five metatarsal bones connect to the proximal phalanges at the joints in the balls of the feet, forming the metatarsophalangeal joints. Each metatarsal bone is referred to by its position relative to the medial side of the foot, the side with the big toe.

The phalanges, or toe bones, are divided into three groups: proximal, middle, and distal phalanges. The big toe, also known as the hallux, has only two phalanx bones: the proximal and distal phalanges. The other four toes have three phalanx bones each. The distal phalanges are the bones at the tips of the toes.

The metatarsal bones and phalanges distribute body weight and facilitate movement. Abnormal weight distribution during sports activities can cause metatarsalgia, a condition characterized by pain in the forefoot. The metatarsal bones and phalanges are also susceptible to injuries, such as fractures and sprains, which can cause significant pain and discomfort.

The Role of the Plantar Plate

The plantar plate is a soft tissue structure that plays a crucial role in supporting the metatarsal bones and phalanges. It is a fibrocartilaginous structure that connects the metatarsal bones to the proximal phalanges, forming a strong and flexible joint.

The plantar plate helps to distribute body weight and facilitate movement by absorbing shock and reducing pressure on the metatarsal bones and phalanges. It also helps to maintain the alignment of the toes and prevent deformities, such as hammertoes and bunions.

Injuries to the plantar plate, such as tears or ruptures, can cause significant pain and discomfort in the forefoot. Plantar plate injuries can be caused by repetitive stress, trauma, or degenerative conditions, such as osteoarthritis.

Treatment for plantar plate injuries typically involves conservative measures, such as rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE), as well as physical therapy and orthotics. In severe cases, surgery may be necessary to repair or replace the damaged plantar plate.

The metatarsal bones, phalanges, and the plantar plate play a vital role in supporting the forefoot and facilitating movement. Injuries or conditions affecting these structures can cause significant pain and discomfort, and treatment should be sought promptly to prevent further complications.

The Forefoot's Role in Movement

While often overlooked, the forefoot is not just a passenger. It is a key player in the body’s interaction with the ground. It helps:

- Control load distribution as weight shifts forward

- Stabilize the body through sensory feedback and micro-adjustments

- Coordinate with the ankle and toes to transfer force efficiently

- Create lift and flow in gait, not by pushing hard but by guiding and completing the step.

When the forefoot lacks mobility, strength, or awareness, other parts of the body often compensate. This can lead to altered walking patterns, postural imbalances, or discomfort further up the chain.

A Critical Transition Zone

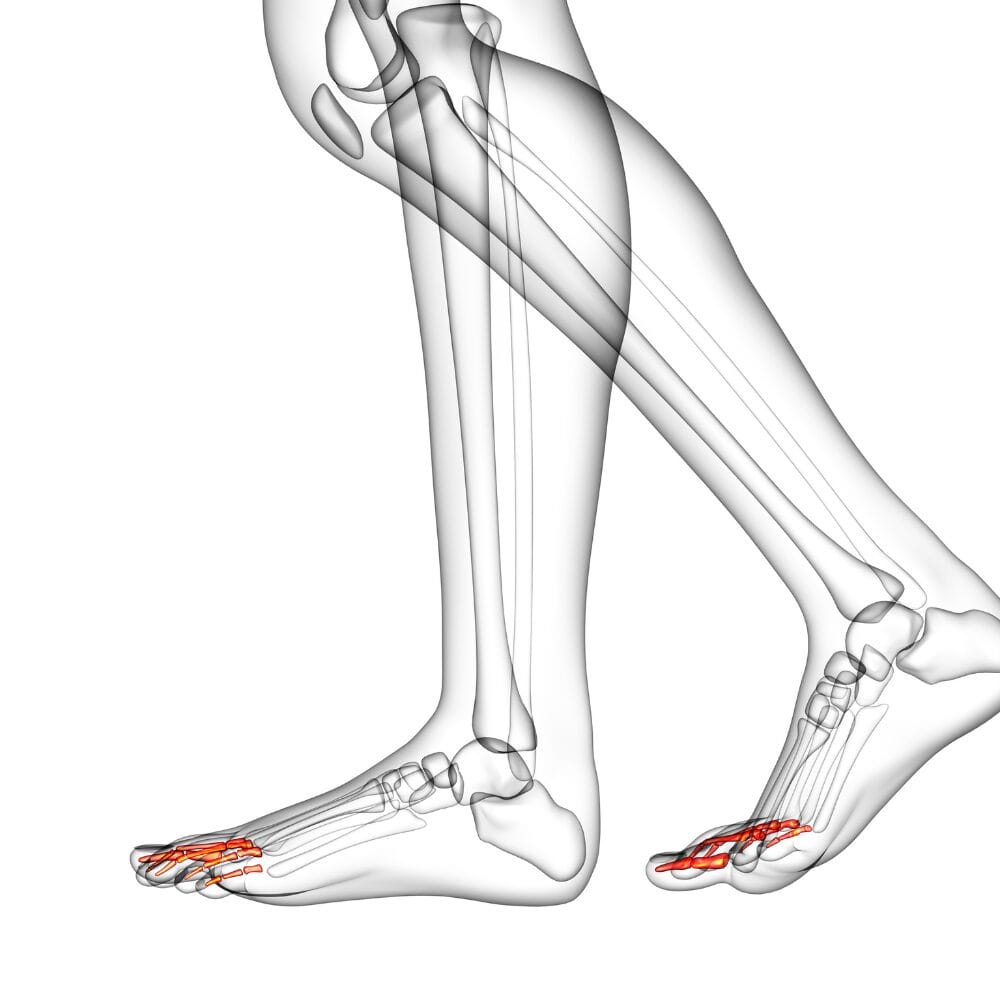

As the body moves forward, weight shifts through the foot, from heel to mid-section, and finally into the front. This area (comprising the metatarsal heads and toes) serves as the final contact point with the ground. It is here that ground reaction forces are negotiated, transferred, and shaped into forward motion.

The first metatarsal plays a crucial role in this process by aiding in weight transfer and maintaining foot stability, particularly in connection with the big toe and the overall mechanics of the forefoot.

This isn’t just about pushing off. It’s about timing, tension, and organization. The front of the foot must be able to articulate and load, acting as both a stabilizer and a release point. This finely calibrated action requires integrity in joint mobility, muscular responsiveness, and fascial continuity.

From Structure to Strategy

The body’s strategy for creating movement through the forefoot hinges on several elements. This region isn’t just the final contact point during walking or running. It plays an active role in transferring load, stabilizing the foot, and integrating whole-body motion.

Issues with one or more toes can significantly affect the forefoot’s ability to transfer load and stabilize the foot, leading to pain and altered movement patterns.

Toe Extension and Arch Integrity

When the toes extend (particularly the big toe), it activates a mechanism that tightens the connective tissue running along the sole of the foot. This is known as the windlass mechanism, which temporarily stiffens the arch. The result is a forefoot that becomes a stable platform for force to be transferred upward and forward, rather than collapsing passively into the ground.

Foot deformities, such as hallux valgus, can significantly impact toe extension and arch integrity. Hallux valgus, the most common foot deformity, often results from restrictive footwear and other contributing factors, leading to compromised foot mechanics.

Ankle Sequencing and Coordination

The ability of the ankle to contribute through plantar flexion (pointing the foot downward) works in harmony with the forefoot’s loading phase. If this coordination is off, the movement becomes disjointed and less efficient. Energy is either lost or rerouted through joints and muscles not designed to handle the load, which may lead to strain or compensation patterns elsewhere.

Poor coordination and load transfer can result in shooting pain in the forefoot, particularly in the toes or the ball of the foot. This type of pain often worsens with activities like walking or running and can be linked to underlying causes such as nerve inflammation or weight distribution issues.

Integration Through the Kinetic Chain

The fascia, musculature, and nervous system all help link forefoot mechanics to the rest of the body. The tension generated in the sole of the foot connects to the calf, hamstrings, pelvis, and spine. When the forefoot functions well, it enhances the entire system, improving balance, fluidity, and alignment with each step.

The proximal phalanx plays a crucial role in joint mechanics, impacting the function of the forefoot and contributing to overall movement efficiency.

Practitioner Cues: Engaging the Front of the Foot

These simple, effective cues help clients engage the forefoot with more awareness and control. Use them during sessions to reinforce movement quality and postural support.

“Let your toes feel the ground, not just touch it.”

What it does: Encourages conscious sensory engagement and subtle weight awareness through the forefoot without tension or grip.

When to use it: Great for grounding exercises, barefoot work, or balance training. Especially with clients who under-recruit their foot intrinsics or move too quickly through the gait cycle.

Therapist note: This cue promotes proprioception and supports nervous system regulation by enhancing body-ground dialogue.

“Lift through the crown, push through the pads.”

What it does: Links vertical posture with lower-body engagement, aligning the sense of upward lift through the spine with downward contact through the front foot.

When to use it: Ideal for walking drills, split stance work, or any closed-chain upright movement where you want to integrate posture and ground mechanics.

Therapist note: Works well with clients who disconnect their foot mechanics from trunk control or collapse into the floor during movement.

“Press, don’t spring.”

What it does: Encourages an intentional, timed transition of force through the front of the foot, avoiding reactive or uncontrolled push-off.

When to use it: Perfect for gait retraining, running drills, and any time you’re working with a client with excess tension or overdrive in their movement patterns.

Therapist note: Helps shift movement strategy from power-based to precision-based, useful in rehab and postural re-education.

“Let the toes spread before you rise.”

What it does: Activates the intrinsic foot musculature and encourages a stable, adaptable base prior to upward motion.

When to use it: Before squats, heel raises, or gait work. Excellent for clients who show poor balance, early heel lift, or collapse through the midfoot.

Therapist note: This cue helps restore natural foot mechanics often lost from years of wearing narrow or rigid footwear.

“Push the floor away, don’t launch off it.”

What it does: Frames the foot’s role as a responsive partner to the ground, not something to push from, but something to push through.

When to use it: Excellent for addressing overdrive, unnecessary tension, or compensatory habits in locomotion.

Therapist note: This cue supports sequencing and timing of movement, helping clients reduce effort and improve efficiency. It’s especially effective with clients recovering from pain-related gait dysfunctions or those needing to re-establish trust in load-bearing patterns.

Common Disruptions in Forefoot Function: Addressing Forefoot Pain

Issues in the forefoot often go unnoticed until something further up the body starts to hurt or feel off. Because this region plays a key role in load transfer and movement coordination, even minor dysfunctions can ripple outward into noticeable limitations elsewhere.

The anatomical structure of the five toes is crucial for proper forefoot function. Four of the five toes comprise three phalanx bones, while the big toe includes only two. Issues with these toes can lead to significant disruptions in forefoot function.

Some of the most common disruptions include:

- Collapsing arches or forefoot instability: When the forefoot lacks a stable foundation, the arch often collapses under load. This can compromise the windlass mechanism, reduce efficiency in push-off, and create excessive stress in the midfoot and ankle.

- Limited toe extension (especially of the big toe): Without adequate toe mobility, particularly at the first metatarsophalangeal joint, the forefoot cannot properly engage during the late stance phase. This restriction reduces stride length and alters gait mechanics.

- Rigid or narrow footwear: Shoes that limit forefoot movement, especially toe splay, can inhibit natural loading patterns, reduce sensory input, and weaken the intrinsic foot muscles over time.

These mechanical disruptions may not feel like foot problems at all. Instead, they often show up in the form of:

- A shortened stride: Clients may feel like they are shuffling or not walking as freely, often without knowing why.

- Over-reliance on hip flexors: When forefoot engagement is compromised, the hips may pull the body forward. This can lead to overuse and tightness.

- Persistent knee or lower back strain: Poor forefoot function can disrupt shock absorption and force transfer, causing strain to accumulate higher up the kinetic chain.

- Fatigue during walking or light exercise: Each step requires more effort without efficient forefoot mechanics. This often leads to early fatigue, even in people who appear otherwise fit.

These are not just “upstream” issues. They often stem from the underuse, stiffness, or misalignment of the forefoot, which is rarely given the attention it deserves.

Practitioner Insight

The forefoot often reveals subtle clues about load transfer and movement control. Use the following observations to assess its role in whole-body mechanics.

Assessing Ground-Lever Efficiency at the Front of the Foot

In clinical or movement-based settings, subtle observations of this region can reveal significant neuromechanical insights. Consider including the following in your assessments:

First Ray Mobility

Limited dorsiflexion of the first ray (1st metatarsal) can restrict the ability to load efficiently, affecting the windlass mechanism and leading to compensatory push strategies through the lesser toes.

Toe Extension Timing

Early or delayed toe extension during terminal stance may suggest altered sequencing. This can indicate either premature offloading due to instability or excessive reliance on posterior chain tension.

Forefoot Splay and Load Distribution

Use a pressure plate or simple visual cues (like barefoot gait on a mirror box) to observe how the load is distributed across the metatarsal heads. A dominant medial or lateral load may suggest patterns of imbalance up the kinetic chain.

Footwear Habituation

Clients habituated to stiff soles and restricted toe boxes often present with reduced intrinsic foot tone and passive push-off strategies. Rehabilitative strategies should involve graded reintroduction to barefoot or minimalist loading where appropriate.

Functional Tasks

Challenge the region with tasks such as single-leg toe-off holds, controlled forward lunges, or barefoot balance drills. Watch for compensation through tibial rotation, knee valgus, or hip elevation, often pointing to foot-ground inefficiencies.

Why the Forefoot Matters for Everyone

For Practitioners:

Assessing the forefoot offers a valuable lens into the body’s overall movement strategy. Watch how weight transfers across the metatarsals. Look for delayed or absent toe extension. Note if the forefoot engages during gait or if the person is lifting and falling through the step. These subtle signs often explain long-standing compensation patterns elsewhere.

Simple, functional assessments such as barefoot walking, heel raises with toe awareness, or step-to-stand transitions can reveal a great deal about forefoot control and its influence on posture, gait, and stability.

For the General Public:

You do not need to be a professional to explore your forefoot mechanics. Try walking barefoot at home and paying attention to whether your toes splay naturally, grip the floor, or remain rigid. Notice if your steps feel smooth and continuous or if they feel choppy and disconnected.

These are more than passing observations. They offer real clues about how your body organizes itself with every step. Improving forefoot awareness can lead to more graceful, balanced, and efficient movement throughout your day.

Key Takeaway

The forefoot is not simply the last part of your foot to touch the ground before lift-off. It is a finely tuned interface that helps initiate, transfer, and sustain movement across the entire body.

We do not just improve foot mechanics by restoring strength, mobility, and awareness in this region. We shift the entire conversation between the body and the ground. This means better posture, smoother motion, and a more integrated experience of walking, standing, and moving through the world.

Try This: 3 Ways to Wake Up the Front of Your Foot

These practical exercises are designed to wake up the forefoot, improve balance, and build awareness—all with minimal time and no equipment.

- Go Barefoot (Mindfully)

Spend a few minutes each day walking barefoot on a firm surface. Focus on how your weight moves across your foot. Do your toes spread and engage, or do they stay passive? Awareness is the first step toward improvement.

- Toe Taps and Lifts

While seated or standing, press your toes into the ground without curling them. Then, lift them while keeping the ball of your foot grounded. Alternate slowly. This helps strengthen small foot muscles and reconnects neural pathways that support balance and stride efficiency.

- Controlled Heel Lifts

Stand tall and slowly lift your heels off the ground, rising onto the balls of your feet. Pause briefly, then lower with control. Keep your toes spread and avoid rolling out or collapsing in. You’re training strength, stability, and coordination all at once.

FAQ's Frequently Asked Questions

How does the front of the foot affect posture?

The front of your foot is a key player in moving and standing. As you shift weight forward, this part of your foot helps manage balance and creates a ripple effect through your legs, hips, and spine. When it’s not doing its job well due to stiffness, weakness, or lack of awareness, your posture can suffer, and the rest of your body may start to compensate.

What are the best exercises to activate the front of the foot?

Think simple and consistent. Try slow heel raises, barefoot walking at home, toe spreads, or seated toe taps. These small drills can wake up the muscles in your foot and improve your connection to the ground. Just a few minutes a day can improve stability and make walking feel smoother.

Why do my toes matter when I walk? The Role of the Big Toe

Your toes help guide your step and stabilize your stride. When they’re active and responsive, they create a more efficient transition from one step to the next. If they’re stiff, inactive, or cramped from tight shoes, you might start to feel strain in your legs, hips, or lower back, even if your feet don’t hurt.

What do practitioners look for when assessing foot mechanics?

Practitioners often pay attention to how your foot moves as a whole, especially how you shift weight forward. They might check how your toes move, whether your foot collapses inward or outward, and how you rise onto the ball of your foot. These subtle movements give clues about posture, coordination, and movement habits.

Can improving the front of the foot help with balance and stability?

Yes. Often more than people expect. The front of your foot helps you adjust to changes in surface and direction. Your body becomes more stable, grounded, and responsive when strong and engaged. This is especially helpful as we age or recover from injury.

Is it ever too late to improve how your foot functions?

Never. Whether you’re in your 30s, 60s, or beyond, your body is always adapting. With gentle, consistent movement practices, like mindful walking, balance work, or simple foot exercises, you can reawaken dormant muscles, improve coordination, and feel more grounded. Progress might be gradual, but it’s always possible.

Resources

Articles:

Anatomy and Biomechanics of the First Ray

Authors: Ward M. Glasoe, H. John Yack, Charles L. Saltzman

Description: Published in Physical Therapy (1999), this study explores the first ray’s role in foot mechanics, focusing on its structural importance within the medial longitudinal arch. It highlights how pronation and supination during gait stabilize the arch and prepare the foot for propulsion, emphasizing the first ray’s role in load-bearing and weight transfer

The Foot Core System: A New Paradigm for Understanding Intrinsic Foot Muscle Function

Authors: Patrick O. McKeon, Jay Hertel, Dennis Bramble, Irene Davis

Description: Published in British Journal of Sports Medicine (2015), this paper introduces the concept of the “foot core system,” which integrates passive structures (bones and ligaments), intrinsic muscles, and neural components to stabilize foot arches during dynamic activities. The study emphasizes the importance of intrinsic muscles in controlling arch deformation and maintaining efficient movement.

PLEASE NOTE

PostureGeek.com does not provide medical advice. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical attention. The information provided should not replace the advice and expertise of an accredited health care provider. Any inquiry into your care and any potential impact on your health and wellbeing should be directed to your health care provider. All information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical care or treatment.

About the author

Join our conversation online and stay updated with our latest articles.

Find Expert Posture Practitioner Near You

Discover our Posture Focused Practitioner Directory, tailored to connect you with local experts committed to Improving Balance, Reducing Pain, and Enhancing Mobility.