Mouth Breathing and Posture in Children: The Hidden Feedback Loop

- Updated - September 3, 2025

When you picture a child at rest, you probably imagine a calm face, lips closed, breathing quietly through the nose. Yet many children do not fit this picture. Instead, their mouths hang slightly open, the breath passes through parted lips, and their chest rises high with each inhale.

At first glance, this might not seem like a big deal, just a quirky habit or a response to a stuffy nose. However, chronic mouth breathing is much more than that. It sets off a cascade of changes that affect not only breathing but also posture, growth, movement, sleep, and even behavior.

This post takes a deep dive into how posture and mouth breathing form a bi-directional feedback loop. Understanding this loop helps parents, practitioners, and educators see why early intervention matters and why solutions must look beyond the airway alone.

Why Mouth Breathing Matters

The human body is designed for nasal breathing. The nose filters, warms, and humidifies incoming air. It also regulates airflow and nitric oxide production, supporting oxygen delivery and immune defense.

When the mouth becomes the primary breathing route:

- The airway often narrows.

- Oxygen exchange becomes less efficient.

- The tongue loses its natural resting place against the palate.

- The muscles of the head, neck, and chest adapt in ways that distort posture.

For children, whose bones and soft tissues are still developing, the effects are magnified. Mouth breathing can influence jaw growth, dental alignment, and even the shape of the face. Less obviously, it alters movement, concentration, and emotional regulation.

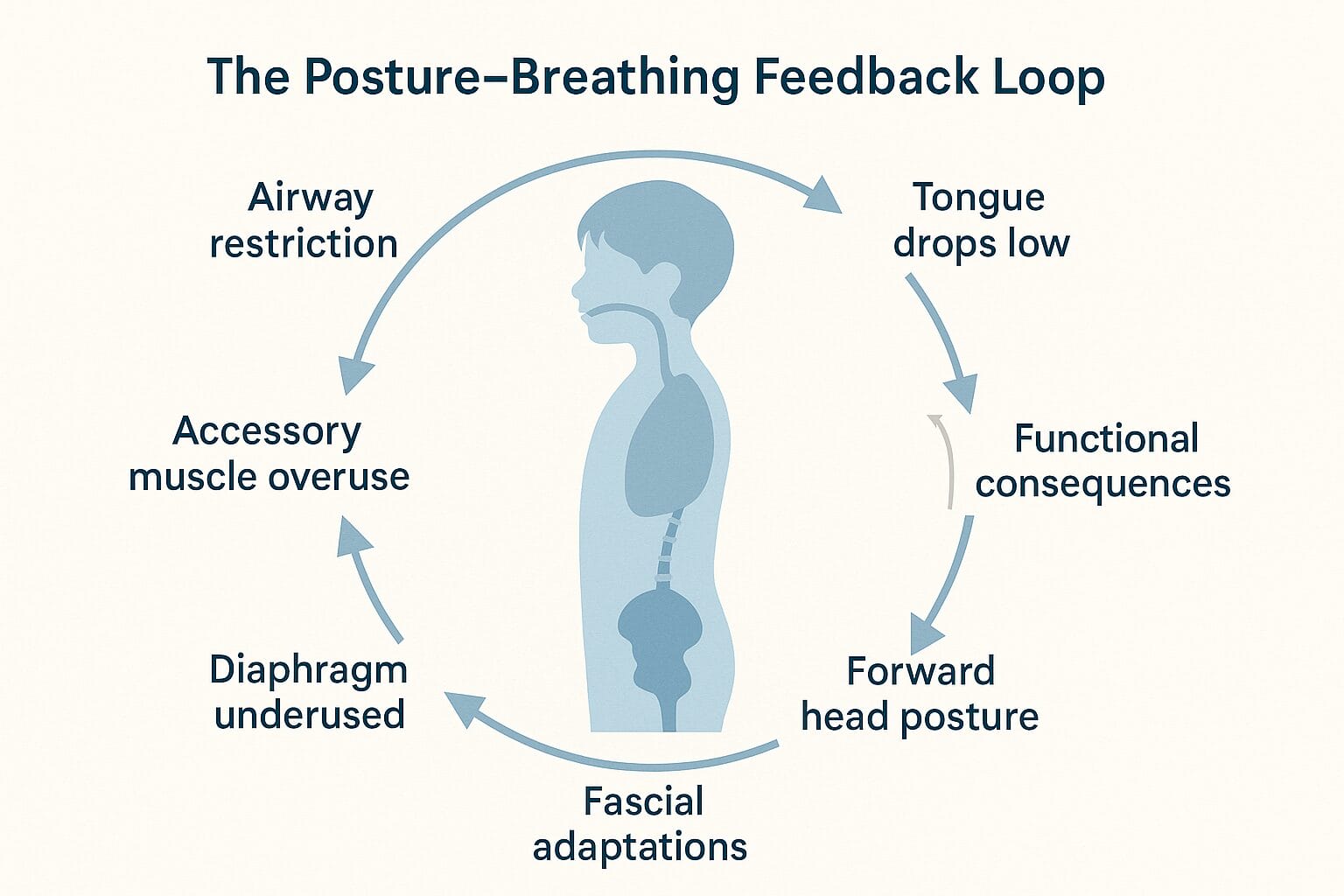

The Posture - Breathing Feedback Loop

To see how these systems connect, let’s walk through the sequence.

Discover a practitioner near you.

Looking for a practitioner near you? Our extensive network of qualified professionals is here to help you.

1. Airway Restriction

The loop often begins with something blocking or limiting the nasal airway. Common culprits include:

- Allergies

- Enlarged tonsils or adenoids.

- Chronic congestion

- Deviated septum.

Faced with resistance in the nose, the child shifts to mouth breathing. This slight adaptation ripples outward.

2. Tongue Position

Nasal breathing naturally places the tongue against the palate, which helps support the upper jaw. With mouth breathing, the tongue drops low. Over time, this can:

- Narrow the upper jaw and palate.

- Destabilize the bite.

- Encourage the lips and mouth to remain slightly open even at rest.

The jaw and tongue are intimately tied to posture through the hyoid bone and cervical muscles. A low tongue posture sets the stage for structural shifts.

3. Postural Adaptations

To compensate for airway narrowing, children often change head and neck positioning.

- Forward head posture: The head drifts forward, creating space at the back of the throat but straining the cervical spine.

- Chin tilt: Some children extend the chin upward to make breathing easier, overusing the suboccipitals and compressing the upper cervical joints.

- Thoracic collapse: Shoulders round and the chest caves inward, further compromising rib expansion.

These patterns are not random. They are survival strategies to keep air moving, but they come at a cost.

4. Diaphragm vs. Accessory Muscles

Proper nasal breathing engages the diaphragm, which expands the lower ribs and anchors the breath into the core. In mouth breathing:

- The diaphragm is underused.

- The child relies heavily on accessory muscles such as the scalenes, sternocleidomastoids, trapezius, and pectoralis minor.

- Breathing shifts high into the chest.

This creates a “high chest posture” with rib flare and elevated shoulders. It looks like effortful breathing even at rest.

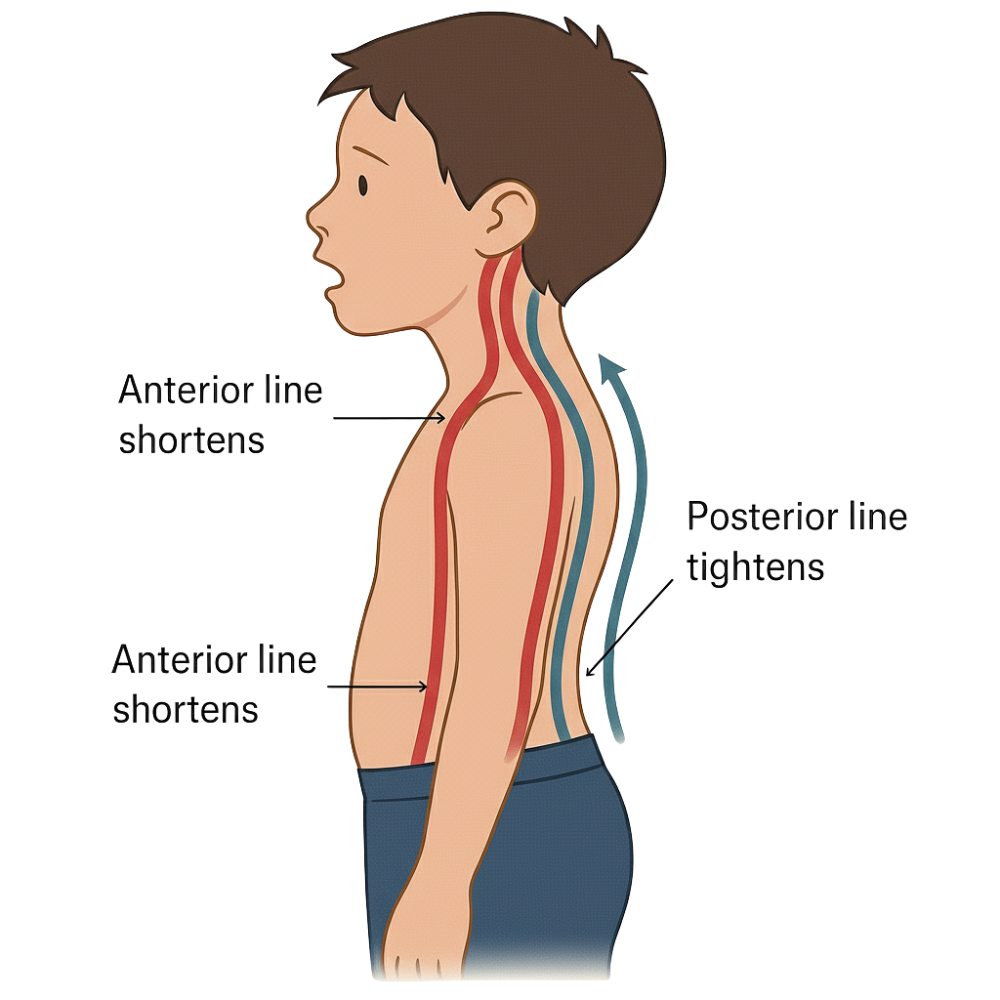

5. Fascial Adaptations

Over time, fascia and fascial lines adapt to these patterns:

- The anterior line (tongue–hyoid–sternum–diaphragm–pelvis) shortens.

- The posterior line (suboccipitals, spinal erectors) tightens in response.

The result is a global postural pattern recognizable to practitioners: open-mouth resting face, forward head, elevated chest, and sometimes a sway-back or compensatory lumbar extension.

6. Functional Consequences

This loop does more than alter appearance. It influences function at every level:

- Sleep: A narrowed airway combined with poor diaphragmatic control increases the risk of snoring and fragmented sleep.

- Concentration: Reduced oxygen exchange and chronic tension affect focus and behavior.

- Movement: A weak diaphragm undermines core stability, reducing efficiency in running, jumping, and coordination.

- Growth: Ongoing airway restriction can shape craniofacial development in lasting ways.

Clinical Signs of Mouth Breathing - Posture Interplay

Parents and practitioners can often spot the signs:

- Lips are frequently apart at rest.

- Visible tension in the neck muscles while breathing.

- Chin slightly tipped up or head projected forward.

- Rib cage lifted high, abdomen hardly moving.

- Complaints of headaches, fatigue, or “tired but wired” behavior.

- Crowded teeth or a narrow palate

For practitioners, palpating fascial tension in the anterior neck or noticing limited rib excursion during breathing assessments can confirm the suspicion.

The Bigger Picture: From Survival to Habit

What begins as a survival strategy, an open mouth to bypass a blocked nose, often becomes a habitual default. Even when the airway is clear, the child’s body has adapted to a new breathing posture system.

This is why addressing mouth breathing requires more than opening the nose. Without retraining posture, tongue position, and diaphragmatic control, the old loop persists.

Breaking the Cycle: Posture - Oriented Strategies

The first step is always a medical evaluation. An ENT should rule out structural airway blockages, and dentists or orthodontists may assess palate development. But alongside this, posture-based interventions are powerful tools.

- Restoring Head and Neck Neutrality

- Chin tuck drills: Involve Gentle retractions against a wall or while lying supine.

- Quadruped play: Crawling and animal movements that naturally align the head over the spine.

- Hanging activities: Monkey bars or supported hanging encourage natural cervical lengthening.

- Diaphragmatic Awareness

- “Belly balloon” exercise: Have the child imagine inflating a balloon in the belly with each inhale.

- Side-lying breathing drills, with a parent’s hand on the lower ribs for tactile feedback.

- Singing or humming with the lips closed promotes nasal airflow and engages the diaphragm rhythmically.

- Tongue-to-Palate Cues

Teaching the child to “rest the tongue roof-tooth” (against the palate, tip just behind the front teeth) helps restore natural oral posture. This can be framed playfully, such as pretending the tongue is a “roof sticker” or “elevator to the top floor.”

- Playful Postural Resets

Children do not respond well to rigid drills, but they thrive with play:

- Crawling races or “animal walks” (bear, crab, lizard).

- Balloon play: blowing up balloons or keeping them afloat with nasal breathing cues.

- Yoga-inspired poses: such as child’s pose, cobra, and bridge, can help open the thoracic space and encourage diaphragmatic activation.

Why Practitioners Must Pay Attention

For posture-focused practitioners, mouth breathing is not just an ENT problem. It is a full-body adaptation. Ignoring the postural side risks incomplete outcomes. Similarly, focusing only on posture without airway assessment misses the root cause.

The integration of perspectives matters:

- ENTs open the airway.

- Dentists and orthodontists support jaw and palate development.

- Practitioners retrain posture, diaphragm, and functional breathing habits.

Together, these interventions can break the feedback loop and restore natural nasal breathing.

A Case Example

Consider an eight-year-old boy who presented with:

- Frequent headaches.

- An open mouth resting face.

- Fatigue at school despite sleeping 10 hours a night.

- Postural changes, including rounded shoulders, forward head, and rib flare.

An ENT referral identified enlarged adenoids, and surgery relieved the blockage. Despite this, his posture and breathing patterns remained unchanged.

Postural retraining was then introduced. The program included gentle chin tuck drills against the wall, balloon breathing with the tongue resting on the palate, and playful crawling activities to support core and head alignment.

Over time, his headaches became less frequent, his posture showed signs of improvement, and teachers reported better classroom focus.

Every child is different, and results will vary. This example is not intended as a prescription but rather to illustrate how combining airway treatment with posture-based strategies can support more sustainable outcomes than relying on a single intervention.

Why this matters

Mouth breathing is not just a quirk. It is a signal that the body is finding a way to navigate the changing situation when the natural nasal pathway is altered. Survival strategies that are left unchecked become lifelong habits with structural consequences.

By understanding the posture–breathing feedback loop, we can:

- Spot early warning signs.

- Support airway and structural interventions.

- Empower children with functional, playful tools to restore nasal breathing.

For practitioners, this is an opportunity to step beyond symptom-chasing and address the integrated system of airway, tongue, posture, diaphragm, and movement.

Finally

Posture and breathing are inseparable. A child who is a mouth breather is not just breathing differently. They are adapting in a way that reshapes their entire musculoskeletal and fascial system.

The good news is that the same body that adapts can also re-adapt. With early awareness, interdisciplinary support, and posture-based strategies, children can reclaim nasal breathing, better sleep, improved focus, and more efficient movement.

The feedback loop can be broken, but only if we recognize it.

Resources

Articles:

Exercise training in children and adolescents with mouth breathing syndrome: a systematic review

Authors: Ana Paula Maçaneiro, Sabrine Nayara Costa, Jonathan Pereira, Karini Borges Santos, Paulo Cesar Bento

Description: A systematic review examining how physical exercise programs, including muscle strengthening, stretching, and diaphragmatic reeducation can improve posture in children and adolescents who habitually breathe through the mouth. All included studies reported postural improvements.

Effects of mouth breathing on facial skeletal development in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Authors: Ziyi Zhao, Leilei Zheng, Xiaoya Huang, Caiyu Li, Jing Liu, Yun Hu

Description: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis that found mouth-breathing children exhibit skeletal changes like a retrognathic mandible, steeper occlusal plane, increased facial height, and narrowed airway dimensions, supporting the anatomical alterations referenced in your discussion.

PLEASE NOTE

PostureGeek.com does not provide medical advice. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical attention. The information provided should not replace the advice and expertise of an accredited health care provider. Any inquiry into your care and any potential impact on your health and wellbeing should be directed to your health care provider. All information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical care or treatment.

About the author

Join our conversation online and stay updated with our latest articles.

Find Expert Posture Practitioner Near You

Discover our Posture Focused Practitioner Directory, tailored to connect you with local experts committed to Improving Balance, Reducing Pain, and Enhancing Mobility.