How the Center of Gravity Shapes Your Posture, Balance, and Movement Strategies

- Updated - November 10, 2025

Most of us have heard the term “center of gravity” (COG) tossed around in fitness classes, physiotherapy sessions, or sports training. But how often do we stop and think about where it actually sits in the body, and more importantly, what it means if that center shifts higher or lower?

In this post, I hope to go beyond the textbook definition and explore how your center of gravity influences your posture, affects your movement strategies, and even guides your body’s long-term adaptations.

Whether you’re a movement enthusiast, a body-aware individual, or a practitioner helping others move and feel better, this lens deserves more attention.

What Is the Center of Gravity?

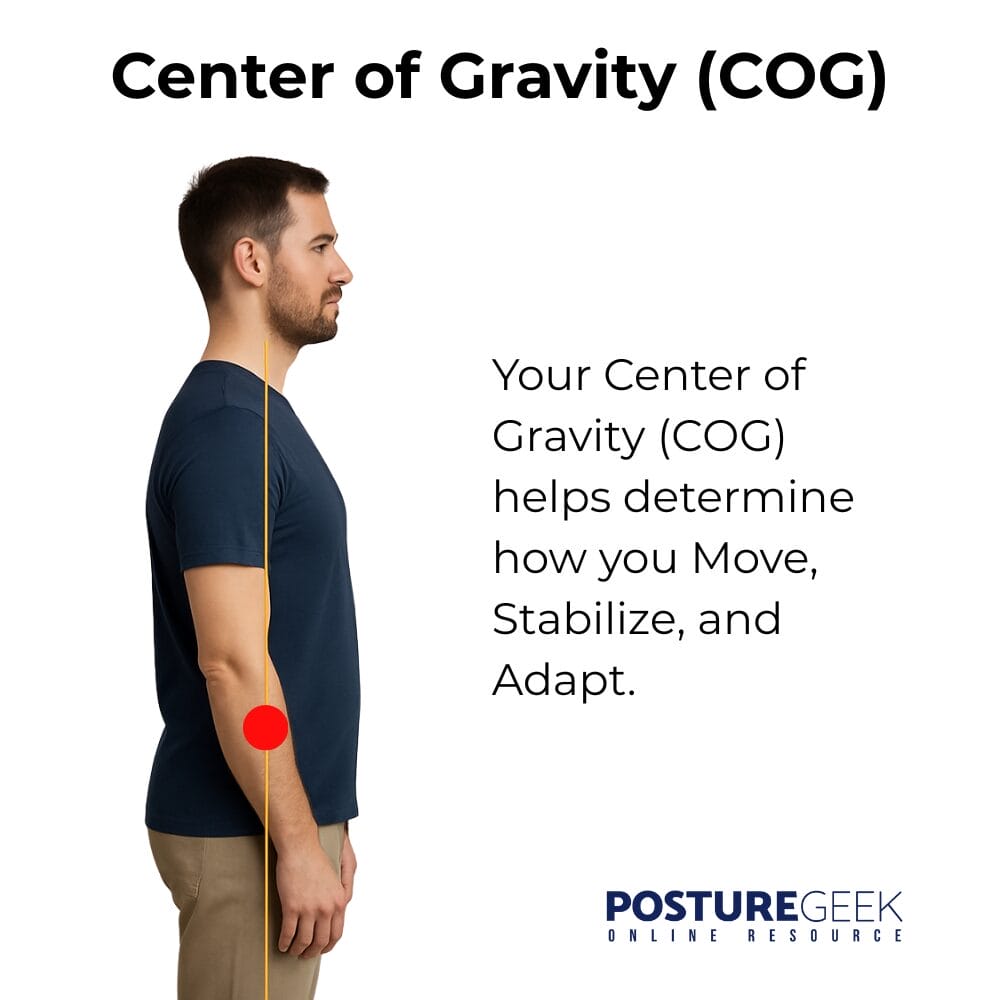

Your center of gravity is the average location of your body’s mass. It’s the point at which gravity is evenly distributed in all directions.

In a simplified anatomical model of the human body standing upright:

- The COG sits just in front of the second sacral vertebra (S2).

- It’s approximately 55% of a person’s height from the ground.

But that’s just a generalization.

Real bodies aren’t symmetrical mannequins. Your COG:

- Shifts constantly as you move.

- It is influenced by body shape, mass distribution, posture, and even learned motor strategies.

- Can be manipulated intentionally, or adapted unconsciously, over time.

And that’s where it gets interesting.

The Body Doesn't Just "Have" a Center of Gravity, It Manages It.

Think of COG as more of a behavior than a location.

The nervous system continually:

- Monitors where your mass is relative to your base of support.

- Adjusts muscular effort to keep you upright.

- Develops movement habits around where your COG tends to sit.

These adaptations become part of your postural strategy. And whether your center of gravity tends to sit higher or lower can have a profound impact on how you move through the world.

Discover a practitioner near you.

Looking for a practitioner near you? Our extensive network of qualified professionals is here to help you.

What Happens When Your Center of Gravity Is Higher?

You can think of a high center of gravity like walking around with a loaded backpack on your shoulders or lifting your arms overhead for long periods. It creates a top-heavy dynamic, and your body must respond accordingly.

Situations That Raise COG:

- Tall stature or long torso

- Upper-body muscle mass (e.g., bodybuilders)

- Carrying weight high (e.g., baby carriers, large breasts, or heavy backpacks)

- Pregnancy (especially the third trimester)

- Arms held overhead (gymnastics, dance, yoga)

- Specific postural adaptations (e.g., rib flaring, lumbar hyperlordosis)

Consequences of a Higher COG:

- Decreased stability: A high COG makes you more prone to swaying or losing balance, especially in narrow stances or on unstable surfaces.

- Greater need for muscular control: The nervous system must work harder to stabilize your trunk and hips, increasing baseline tone in postural muscles.

- Altered movement strategy: The body may stiffen joints or shorten stride to stay balanced. Movements become more cautious and deliberate.

- Increased joint stress: If compensation patterns persist, joints like the lumbar spine, hips, or knees may bear uneven loads over time.

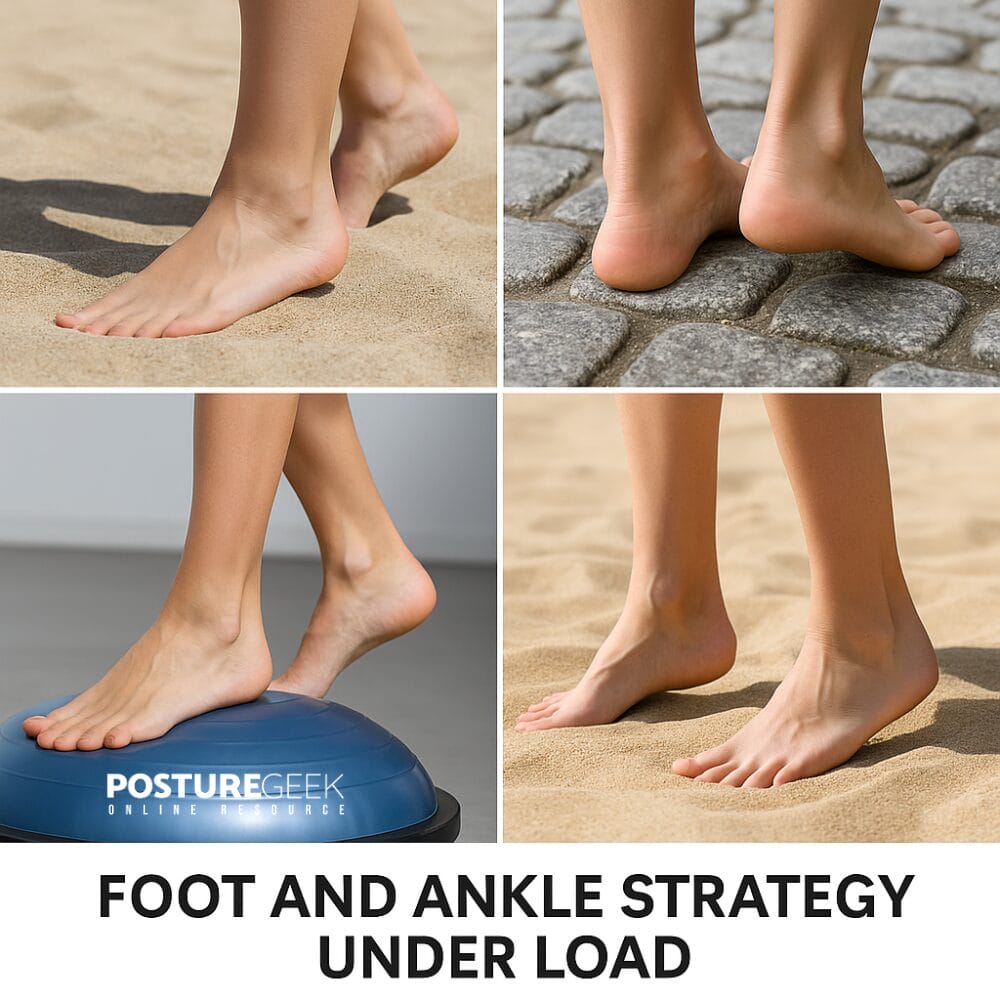

- Foot and ankle overuse: You’ll often see higher-COG individuals using more aggressive ankle or foot strategies to catch themselves, particularly on uneven ground or during sudden transitions.

What Happens When Your Center of Gravity Is Lower?

Imagine doing everything in a deep squat, or picture the groundedness of a sumo wrestler. A lower COG creates a more stable base and often invites more fluid, ground-up movement.

Situations That Lower COG:

- Shorter stature or lower-body dominant builds

- Crouched or wide-stance postures

- Ballet pliés, martial arts stances, or surfing positions

- Excess weight is distributed to the hips and thighs

- Functional movement retraining (e.g., deep squat mobility, hip-hinge drills)

Consequences of a Lower COG:

- Increased stability: A lower COG widens your base of support and lowers the risk of toppling. Great for sports or reactive movement.

- More efficient movement transitions: It’s easier to change direction, absorb impact, and load the hips dynamically.

- Reduced compensatory bracing: With a low COG, the body doesn’t need to stiffen or overuse small stabilizers to maintain posture.

- Potential for slowness or heaviness: If excessively low, it may create sluggish movement or difficulty with upright transitions.

- Stronger emphasis on ground reaction forces: These individuals tend to initiate movement from the feet and hips, using more squat or hinge-driven strategies.

Why This Matters in Real Life

Everyday Example:

Pick up a heavy box and hold it above your head. Now hold it against your waist. The second position feels more stable, right? That’s a simple shift in COG. Now, imagine how your posture and movement strategy adjust to either scenario.

In the Clinic or Gym:

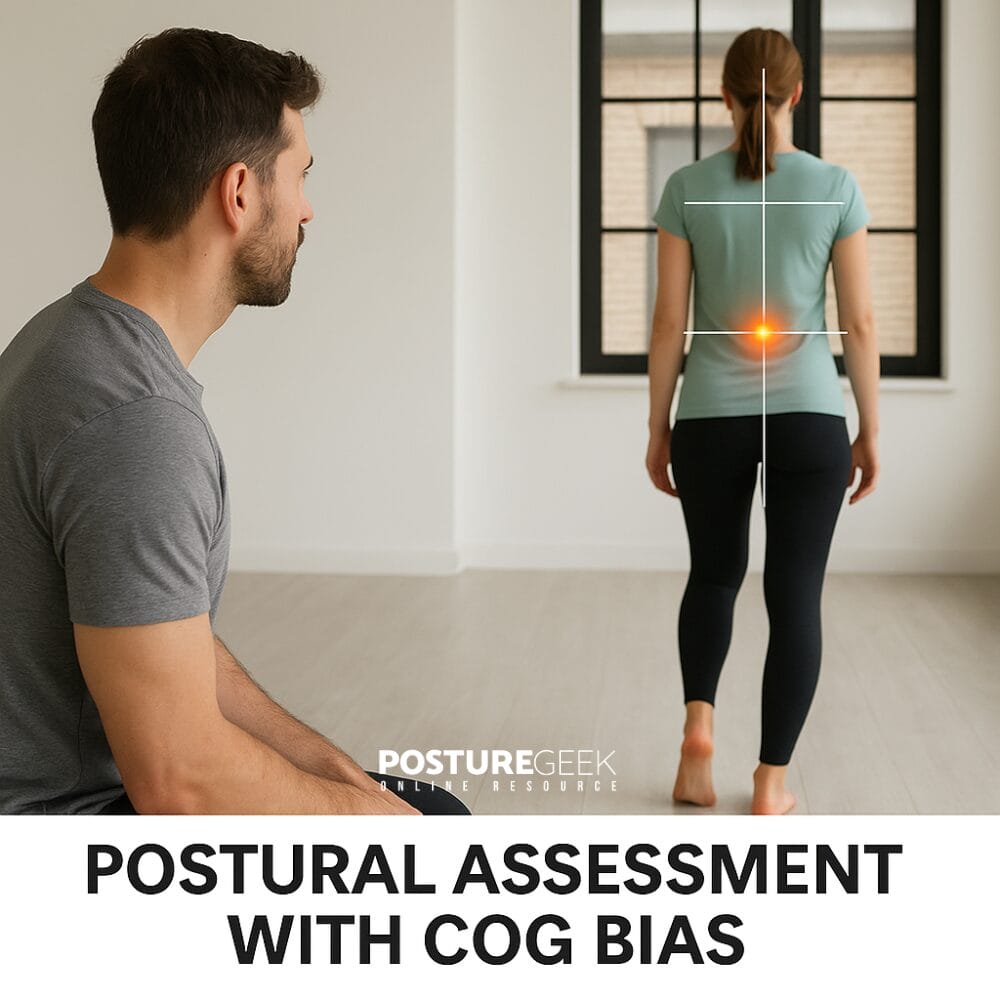

A practitioner assessing someone with balance issues, poor movement efficiency, or recurring strain may be observing the secondary effects of long-term COG habits.

For example:

- A client with a rigid, extended posture and shoulder-dominant breathing may unknowingly keep their COG high and anterior. This can lead to lower back tension and hip instability.

- An athlete with powerful hips and a crouched gait may rely on a lower COG for performance but struggle with thoracic mobility or upright posture.

The Center of Gravity and Posture: It's Not Just Where, But How It's Managed.

This is key.

The COG isn’t just about vertical height. It’s about how your nervous system organizes around it:

- Do you brace up and lift your ribs to feel stable?

- Do you drop your weight low and collapse the spine?

- Do you use momentum to shift your mass because holding control is too effortful?

These are postural strategies, not just positions.

And they become ingrained patterns, adaptations that reflect:

- Fatigue

- Emotional state

- Injury history

- Life stage

- Body image

- Training background

How the Center of Gravity Shifts in Motion.

It’s easy to imagine the center of gravity as a fixed dot inside the pelvis. But in reality, it shifts constantly. The position of your COG isn’t static. It changes with movement, limb position, and how your body distributes effort.

When Standing Upright

- The center of gravity is located just in front of the second sacral vertebra (S2).

- It remains relatively central in the pelvis to maintain balance over both feet.

- In this position, the nervous system makes subtle adjustments to maintain the body’s alignment and upright posture.

When Walking

- The COG moves continuously, side to side, up and down, and slightly forward and back.

- It shifts toward the stance leg during single-leg support.

- Gait becomes a process of managing a moving center of gravity across a shifting base of support.

- Efficient walkers minimize unnecessary sway, whereas those with balance challenges may exhibit exaggerated movement patterns to compensate for their balance issues.

When Running

- The COG lifts slightly higher than in walking and projects more forward.

- The body spends more time in the air, so the center of gravity is less grounded.

- This requires precise counterbalancing through arm swing, core control, and dynamic foot placement to maintain momentum and avoid collapse on landing.

When Rising from a Chair

- The COG starts low and behind the base of support, near or just behind the sit bones.

- To initiate movement, the body must shift that mass forward and upward, typically toward the thighs or abdominal area.

- If the center of gravity doesn’t come far enough forward over the feet, the body won’t be able to rise without falling back.

- This is why sit-to-stand transitions are a common area of difficulty for older adults and a valuable movement to assess in clinical practice.

Practical Implications

For Individuals:

Want to improve your posture, balance, or movement?

Start by noticing where you carry your weight.

- Do you feel tall and rigid, or do you feel collapsed and heavy?

- Is your movement top-down or ground-up?

- Are you over-relying on your toes, shoulders, or lower back?

Play with shifting your COG:

- Try moving with your arms overhead (raises your COG) and notice the compensation.

- Now walk in a deep squat (lowers your COG) and feel the contrast.

- Use movement drills like loaded carries, hip-hinge training, or flow-based work like Animal Flow or crawling patterns to experiment with your body’s response.

For Practitioners:

Whether you’re a physio, movement coach, or manual therapist, the way your client manages their COG can reveal more than a static assessment ever could.

Look for:

- Subtle torso tilts or spinal extensions indicating forward or anterior COG bias

- Persistent tightness in the calves or hip flexors suggests compensation for vertical instability

- Clients who float (hypertonic, upward energy) versus those who sink (hypotonic, collapsed structures)

Tip: Don’t correct COG by cueing alignment alone. Work with dynamic strategies that retrain how the nervous system distributes and responds to load:

- Unilateral loading (e.g., single-leg work, offset weights)

- Transitional drills (e.g., kneeling to standing, floor get-ups)

- Variable stance and surface work (e.g., wobble boards, sand, narrow beam walking)

The Body Is Always Managing Load

Posture isn’t just a shape; many misconceptions about “bad” posture overlook how individual and nuanced our posture truly is.

It’s a solution, a way for the nervous system to manage gravity, stress, and demand with the least amount of perceived threat.

Your center of gravity plays a central role in that equation. It’s not fixed, and it’s not just a vertical issue. It’s influenced by how you think, feel, move, and hold yourself through time.

So the next time you feel off, instead of asking, “Is my posture correct?” consider asking:

“How am I managing my center of gravity right now, and what strategy is my body using to feel safe?”

That question opens a door. Not just to better posture, but to more intelligent movement.

PLEASE NOTE

PostureGeek.com does not provide medical advice. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical attention. The information provided should not replace the advice and expertise of an accredited health care provider. Any inquiry into your care and any potential impact on your health and wellbeing should be directed to your health care provider. All information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical care or treatment.

About the author

Join our conversation online and stay updated with our latest articles.

Find Expert Posture Practitioner Near You

Discover our Posture Focused Practitioner Directory, tailored to connect you with local experts committed to Improving Balance, Reducing Pain, and Enhancing Mobility.